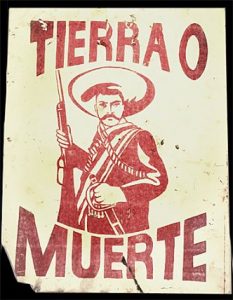

Just before entering Tierra Amarilla, a small town in northern New Mexico located along the Chama River, drivers are greeted by a handmade billboard proclaiming Tierra o Muerte. Perhaps greet is the wrong word. It might be better to say that the phrase is thrust into one’s awareness. It cuts: land or death. Scrawled in thick capital letters, the words ring from a white banner that hangs from three posts. If you’re headed north on Highway 64, the banner would be on the lefthand side of the road; behind it a fence designates private property. Besides the words, there is a silhouette portrait of a mustachioed and bygone Mexican hero. The red cursive script running along the bottom edge reads, “Zapata Vive,” revealing the identity of the looming head to drivers. Brows furrowed, Emiliano Zapata dominates the northern New Mexico roadside.

Zapata was known in the early twentieth century as rebel leader who rallied for land reform in Mexico. An opponent of dictator Porfirio Diaz and provocateur of the Mexican Revolution, Zapata became closely associated with a similar axiom, tierra y libertad (land and liberty). Black and white photographs often portray Zapata donning a large sombrero and a charro outfit with artillery belts crisscrossing his chest.

In late 1960s, at the height of the Chicano Rights movement, a similar image of Zapata was produced and circulated. it was silkscreened onto paper in a format easily made and distributed to large communities. The revolutionary’s image as well as his platform became a call to arms for Chicanos in the town of Tierra Amarilla, where once the courthouse was held hostage, and throughout the Southwest. The highway banner that now occupies the roadside thus draws from two histories: Zapata’s role in the Mexican Revolution and the role of his likeness and legacy in galvanizing the Chicano Rights Movement.

In late 1960s, at the height of the Chicano Rights movement, a similar image of Zapata was produced and circulated. it was silkscreened onto paper in a format easily made and distributed to large communities. The revolutionary’s image as well as his platform became a call to arms for Chicanos in the town of Tierra Amarilla, where once the courthouse was held hostage, and throughout the Southwest. The highway banner that now occupies the roadside thus draws from two histories: Zapata’s role in the Mexican Revolution and the role of his likeness and legacy in galvanizing the Chicano Rights Movement.

Growing up in a small New Mexican village, I heard tierra o muerte often. It was a grito, a call to arms, a lamentation, and a source of cultural pride. Land was a lifeline for my community. It elicited a history that goes back to the era of Spanish colonial land grants when, in the eighteenth century, the viceroy doled out parcels to those willing to colonize the frontier. Land grants were established as colonial buffer zones between New Spain and the Comanche empire. Most of the time, colonists were not valiant Spaniards, but mixed race gente who likely were at the bottom of the rungs of colonial society centered around the early capital of Santa Fe. Sedentary indigenous groups were also confined to land grants, designated plots that allowed Spaniards to capitalize on surrounding real estate. The term land grant can therefore point to how Spaniards doled out lands to colonists, but also to how they circumscribed the territories of others, including many indigenous peoples. In fact, the swaths of land that Spaniards colonized during this era were once Anasazi (early Pueblo peoples), Ute, Navajo, Hopi, Apache, Pomo, and Chumash, to name only a few.

When the U.S. annexed much of Mexico’s territory, in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), the greatest gain was in land. The mostly poor New Mexicans who had once inherited land grant lands from their mixed-raced ancestors centuries prior fought within American courts to keep these collective parcels intact. Much of this fighting took place in the late 1800s, yet in some ways continues still today. Jake Kosek explored the continued struggle over land grant lands with the National Forest in a book, Understories. For the most part, those efforts failed when those courts, the Court of Private Land Claims in particular, used “legal” means to deterritorialize uneducated farmers. It was the case that the legalities of private ownership, according to U.S. law at the time, eluded the mostly Spanish speaking grantees. The National Forest, the railroad, Anglo homesteads and ranches, and now suburbs occupy former land grant lands.

Today, the highway portrait links two moments, New Mexico’s complex history of land, land use and deterritorialization in relation to U.S. national interests, and historical attempts at land reform in Mexico. As the image proclaims, the stakes of losing land were high. One would rather choose death, for the loss of land was the loss of a specific kind of lifeline. In fact, parts of my family on my mother’s side claim land grant lands, specifically the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, San Fernando y Santiago Grant. Stories about these land often involve loss. But they less often include the losses that others have incurred too, and here I think of the original inhabitants of the Southwest.

For me, tierra is evocative of these multiple histories, of land grants, yes, but also of conflict more broadly. I think constantly about how these lands became hispanicized; for some this marks one moment of ethnic pride (including my family’s), but for indigenous groups, this is merely another chapter in a longer timeline of dispossession. Indigenous peoples were, moreover, part of a greater labor force, indeed an indentured labor force, that made colonization possible. Andrés Reséndez wrote an entire book dedicated to the subject. It’s called The Other Slavery.

Thanks, great article.

Good article Keek!